Kenya, like many developing countries, has become the dumping ground for the world’s discarded fashion. Every day, thousands of tonnes of second-hand clothes (commonly known as mitumba) land at the Port of Mombasa, bundled into bales, labelled with unknown names, and sold to traders who flood local markets with foreign garments at a fraction of their original cost.

On the surface, this seems like a good thing: affordable clothes for the masses, thriving informal markets, and job creation but underneath the surface lies a more troubling truth, fast fashion is not just a trend, it’s a trap and Kenya is paying the price.

The second-hand clothing trade in Kenya is valued at over KES 17 billion ($120 million USD) annually and employs hundreds of thousands across the country from port workers to street vendors to market stall owners. Mitumba has become embedded in Kenyan culture, offering everything from luxury-brand knockoffs to high-end thrift finds.

Most of the clothing that arrives is unwearable waste; ripped, stained, or outdated. In fact, up to 40% of the bales imported are considered unusable and end up in open dumpsites or burned, contributing to Kenya’s growing waste management crisis.

According to the Mitumba Consortium Association of Kenya (MCAK), Kenya imports about 185,000 tonnes of second-hand clothing annually equivalent to around 8,000 containers of clothing, shoes, and textiles. What doesn’t get sold often ends up clogging landfills, polluting waterways, or forming piles of synthetic waste that take centuries to decompose.

Oprah endorses Toi Market written and performed by Sitawa Namwalie at CG Studios

Fast Fashion's Global Problem, Kenya’s Local Pain

Globally, the fashion industry is the second-largest consumer of water and responsible for 10% of global carbon emissions, this is more than international flights and maritime shipping combined. As fast fashion brands continue to produce billions of cheap, short-lived garments each year, much of their waste ends up in the Global South.

Kenya, lacking the infrastructure to process or recycle this avalanche of textile waste, becomes a fashion landfill. An environmental burden, borne by local communities that is invisible to most Western consumers.

Meanwhile, local textile industries have collapsed under the weight of cheap imports. Once-vibrant sectors like KICOMI (Kisumu Cotton Mills) and RIVATEX that supported Kenyan cotton farmers and factory workers have struggled to compete. Local designers, tailors, and seamstresses are priced out by low-cost alternatives, despite having the creativity and skill to build a sustainable fashion economy from the ground up.

So What’s the Solution?

It starts with rethinking value.

Kenya is home to a new wave of designers, artists, and entrepreneurs working to reclaim fashion through upcycling, sustainable design, and slow fashion principles. Platforms like ours are supporting young creatives who transform second-hand clothes into costumes while telling stories of resistance, resilience, and resourcefulness.

Educational programmes around fashion waste, environmental sustainability, and circular design are on the rise. Consumers are also becoming more conscious, slowly shifting away from buying trends to buying meaning.

Fast Fashion Isn’t Free, It Just Hides Its Costs

While mitumba remains a lifeline for many Kenyans, it’s clear that fast fashion's global system is unbalanced and unjust. The real cost is borne by the environment, by workers, and by local industries that struggle to stay afloat.

As Kenya confronts the dual challenges of poverty and pollution, one thing is clear: we must rethink how we dress, consume, and value our clothes. Not just for ourselves, but for our communities, our environment, and the generations to come.

There Is No Planet B

Fashioning a Future Beyond Waste

A curatorial statement

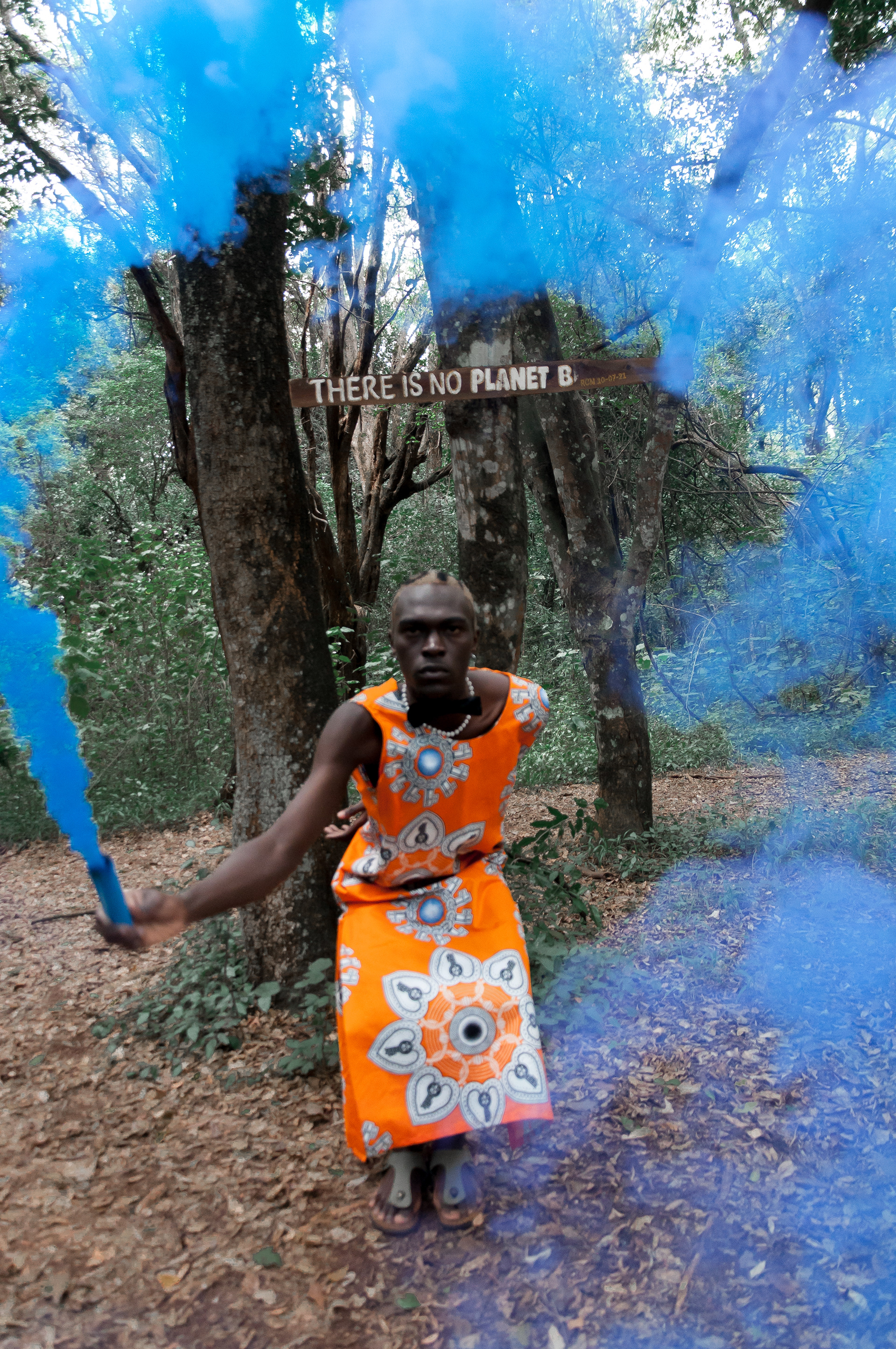

In this provocative and visually arresting body of work, There Is No Planet B confronts the urgent and unsettling realities of fast fashion through the lens of artistic reclamation. Conceived in collaboration with a collective of Nairobi-based artists and commissioned by Creatives Garage, the project emerges as both protest and proposal: a reimagining of fashion’s place in a world teetering on ecological collapse.

Today’s aesthetic culture celebrates consumption; wardrobes curated for admiration, silhouettes designed for fleeting moments of validation. Yet, behind this curated image lies an industry built on exploitation: underpaid garment workers laboring in unsafe conditions; materials sourced through extractive, unsustainable processes; and garments discarded after only a handful of uses, only to resurface in third-world economies as bulk waste, repackaged and resold, often unwearable.

There Is No Planet B responds to this crisis not with despair, but with transformation. Using salvaged off-cuts and textile remnants from Nairobi’s tailoring community, the artists construct a series of androgynous, post-consumer garments, each piece an act of resistance against mass production and disposability. The garments are not merely worn, but inhabited, styled and photographed in imagined futures where fashion is ethical, circular, and conscious.

The resulting photographic series functions as both documentation and metaphor: a study of the body in reclaimed space, of identity unstitched from capitalism’s seams. It challenges viewers to reflect on their complicity in the global fashion cycle and invites them into a new dialogue, one that is rooted in sustainability, craft, and intentional creation.

There is no Planet B is a call to imagine, to wear, and to create otherwise.

Created by @Thayu

Photography by @le.drew_

outfits by Nyambura Mwangi

Muse @Juma Jatteh